Research Briefs

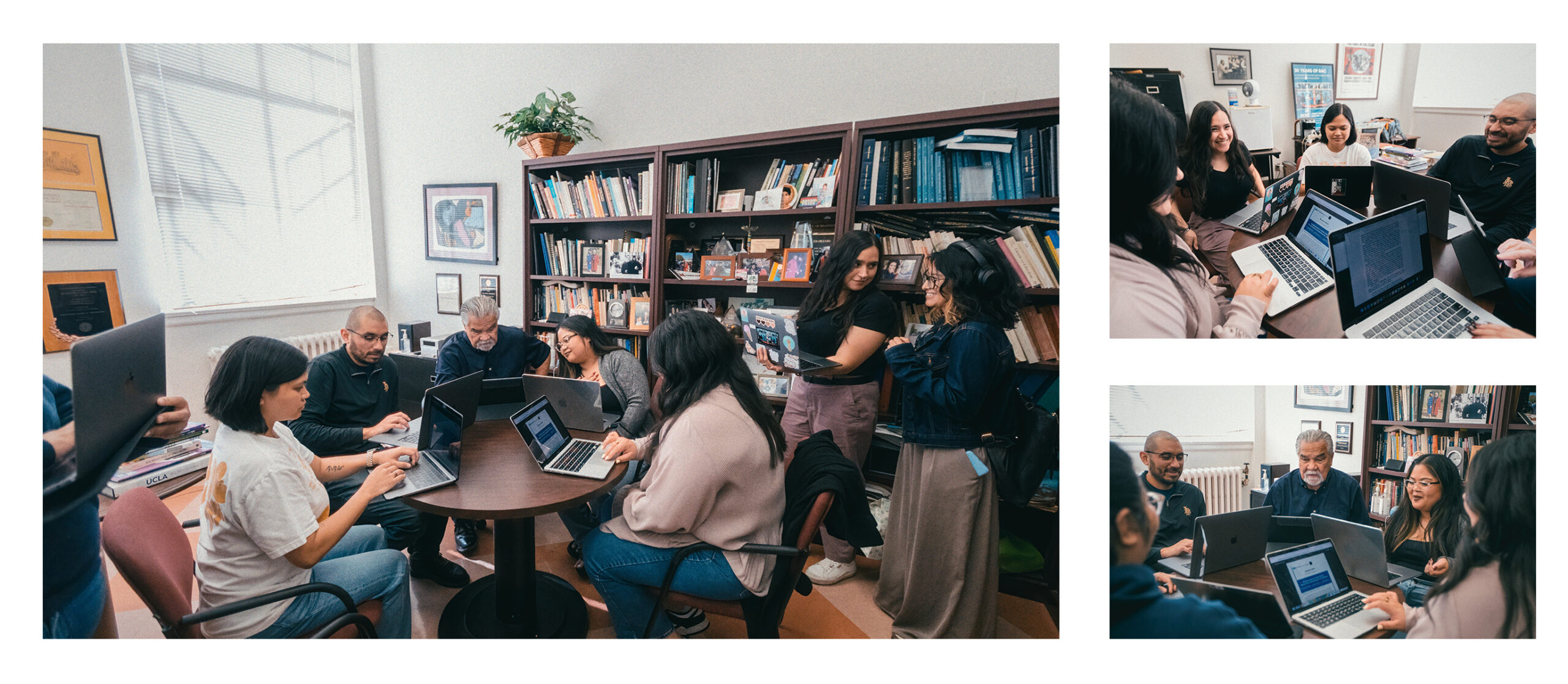

The Center for Critical Race Studies in Education (CCRSE) at UCLA’s inaugural Research Briefs Series was released in June 2016 with a total of five issues. In June 2017 the second CCRSE Research Briefs Series was published with an additional six issues. As of 2025, a total of 21 Research Briefs have been published, they explore: cultural intuition, racial battle fatigue, racial microaggressions, critical race history methodology, community cultural wealth, internalized racism, muxerista portraiture, critical race counterspaces, Asian American Critical Race Theory, critical race educational history, critical race spatial analysis, Chicana/o student activism in Los Angeles, intersectionality, holistic critical race pedagogies, and racial microaffirmations. Please click on the “Read this Issue” button under each brief to view the full issue.

Recently Published

Conceptual Briefs

Cultural Intuition: Then, Now, and Into the Future

Dolores Delgado Bernal

University of Utah

Cultural intuition, deeply informed by Chicana feminist scholarship, was first introduced to the field of education in 1998 to reimagine the notion of theoretical sensitivity (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). Working from a Chicana feminist episteme, Delgado Bernal (1998) proposed that cultural intuition, the unique viewpoint that many Chicanas bring to the research process, draws from personal experience, collective experience, professional experience, communal memory, existing literature, and the research process itself.

Read this issue

Understanding the Corollaries of Offensive Racial Mechanisms, Gendered Racism, and Racial Battle Fatigue

William Smith

University of Utah

One of the most significant and persistent concerns for Communities of Color is the effect of racism. People of Color are constantly stressed from the burdens of defending their humanity and existence. Rarely are the diversities and intersectionalities of their humanness considered, as they are forced to respond to how dominant White society sees and treats them: as a racial group only. For example, a socially identified Puerto Rican woman might see herself not only at the intersections of race and gender but also at intersections of class, physical impairment, sexuality, phenotype, ethnicity, and languages.

Read this issue

Micro in Name Only: Looking Back to Move Forward in Racial Microaggression Research

Kenjus T. Watson

University of California, Los Angeles

Lindsay Pérez Huber

California State University, Long Beach

Racial microaggressions are a form of systemic racism that (a) are verbal and non-verbal assaults directed toward People of Color*, often carried out automatically or unconsciously; (b) are based on a Person of Color’s race, gender, class, sexuality, language, immigration status, phenotype, accent, or surname; and (c) are cumulative, taking a physiological, psychological, and academic toll on those targeted by them (Pérez Huber & Solórzano, 2015a; 2015b). In 2014, college students across the US thrust the concept of racial microaggressions into public discourse with social media campaigns to call attention to the everyday racism Students of Color encountered on their college and university campuses. Racial microaggressions quickly became a term to explain experiences with racism in a “post-racial” era. Since then, numerous scholars and columnists have challenged racial microaggressions to argue that this concept attributes to the “coddling” and “hypersensitivity” of U.S. college students that can create a “vindictive protectiveness” that impedes student learning in higher education (Gitlin, 2015; Lukianoff and Haidt, 2015). The characterization of racial microaggressions as “vindictive” illustrates the lack of understanding about the theoretical origins of this concept, developed over 40 years ago by African American psychiatrist, Dr. Chester Pierce.

Read this issue

Reclaiming Our Histories, Recovering Community Cultural Wealth

Tara J. Yosso

University of Michigan

Rebecca Burciaga

San Jose State University

Critical race theory (CRT) is a dynamic interdisciplinary framework used to identify, analyze, and challenge the ways race and racism intersect with multiple forms of subordination to shape the experiences of People of Color (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012). Informed by critical community and academic traditions naming race as a social construction, scholars have applied CRT to the field of education to closely examine and change the very real social consequences of racism within and beyond schools (e.g. Zamudio, et al., 2011; Parker & Stovall, 2004). Collectively, this work has taken up Richard Delgado’s (2003) challenge to “consider that race is not merely a matter for abstract analysis, but for struggle. It should expressly address the personal dimensions of that struggle and what they mean for intellectuals” (pp. 151-152). In this brief, we focus on the naming an array of knowledges, skills abilities, and networks of communities of color “not merely for abstract analysis,” but as a part of the larger struggle to survive and resist racism.

Read this issue

Internalized Racism: The Consequences and Impact of Racism on People of Color

Rita Kohli

University of California, Riverside

Although heightened by the current hate-filled platform of the 45th U.S. President, scholars of Critical Race Theory (CRT) have exposed racism as a permanent failure in the policies and practices that govern U.S and other settler colonial and colonial societies. As people of Color are subjected to racialized structures in their daily lives, racism can have material, physiological, and psychological consequences that negatively affect the matter by which they see themselves, their culture, and the world around them.

Like racism, internalized racism is real and pervasive, but because peoples’ self and worldviews are fluid and ever changing, it can be problematic to pathologize someone as embodying or “having” internalized racism. Instead, internalized racism must be understood as a learned or indoctrinated perspective, something complex and shifting in its manifestation. In addition, internalized racism is not a permanent state, as it can be mitigated by an access to critical history, a cultivation of self and community love, and a heightened understanding or analysis of racism.

Read this issue

Spatializing Race and Racializing Space: Exploring the Geographic Footprint of White Supremacy Using Critical Race Spatial Analysis

Verónica Vélez

Western Washington University

DuBois (1903) first articulated the notion of the “color-line?” more than 100 years ago. Still significant today, DuBois’ work inspired the development of Critical Race Spatial Analysis (CRSA). First conceived in 2007, CRSA emerged as part of a case study of one of the most robust color-lines in Los Angeles, California – the Alameda Corridor (Solórzano & Vélez, 2007). By utilizing maps to reveal the socio-spatial-historical significance of the Alameda Corridor, this study motivated a pursuit to further digital map-making and other geographic and spatial tools within Critical Race research in education. An evolving framework, CRSA examines the role of race and racism in geographic and social spaces and works toward challenging racism and all forms of subordination within these spaces, particularly those within and connected to schools (Vélez & Solórzano, 2017). Rooted in Critical Race Theory (CRT), CRSA spatially explores how structural factors shape racial dynamics and the power associated with those dynamics over time. Within educational research, CRSA is particularly interested in how space is divided, constricted, and constructed along racial lines to impact educational experiences and opportunities. CRSA attempts to answer the following: 1) How do race and racism shape space, give it meaning, and condition the experiences of Communities of Color’?; 2) How can digital mapping spatially analyze race and racism?; and, 3) What pedagogical possibilities does CRSA hold for teaching and learning about the relationship between race and space?

Read this issue

Intersectionality: A Genealogy Of Black Feminist Freedom Visioning

Mary Senyonga

University of California, Los Angeles

Intersectionality as a methodological, analytical, and liberatory tool has sharpened our naming of multiple forms of marginalization. While Kimberle Crenshaw (1989, 1993) is rightfully credited with coining Intersectionality through addressing Black women’s employment experiences and other Women of Color’s experiences with domestic violence, it is imperative that we recognize the long history of this articulation of marginalization. Within the Black feminist tradition, Black women have named the liminal space of being called to action on behalf of racial or gender liberation while our liberation is relegated as adjunct to others’ (Combahee River Collective, 1977). My aim in this brief is to name and celebrate the genealogy of Black feminist resistance by highlighting activist Florynce Kennedy and Crenshaw’s use of a Black feminist framework to approach the law as well as meditate on futures that can be animated from articulating a simultaneity of marginality that provides a more nuanced understanding of experiences of interlocking domination.

Read this issue

Racial Microaffirmations as a Response to Racial Microaggressions

Lindsay Pérez Huber

California State University, Long Beach

Critical race researchers have theorized and documented the varied ways that racial microaggressions are used to keep those at the racial margins in their place (Pierce, 1970). Racial microaggressions are (1) verbal and/or non-verbal assaults directed toward People of Color, often carried out in subtle, automatic or unconscious forms, (2) layered, based on race and its intersections with other subordinated social identities and, (3) cumulative, taking a psychological and physiological toll on People of Color when experienced over a lifetime (Pérez Huber & Solórzano, 2015). Naming racial microaggressions disrupts the normalized existence of racism and white supremacy, and recognizes the structural inequities and collective pain they cause (Freire, 1970). Equally important, is theorizing and creating a language for the everyday strategies of affirmation and validation that Communities of Color engage as a response to racial microaggressions. This brief seeks to begin this theorizing.

Read this issue

Chicana M(other)work: A Conceptual and Collective Framework

Michelle Téllez

University of Arizona

Chicana M(other)work is both a conceptual framework and a call to collective action that responds to the gaps in the Chicanx’ educational pipeline? that begin in elementary school and continue to affect the life chances of Chicanx students. This brief focuses on Chicanas in higher education who are not adequately represented in the literature by paying particular attention to the inequities experienced by Chicana and Latina mothers who are both seeking advanced degrees and academic appointments after graduate school.

#BLM Mamas’ Motherwork: Conceptualizing the Critical Race Socialization of Black Children

Janay M. Garrett

University of Pennsylvania

In this research brief | outline what I call the Critical Race Socialization (CRS) of Black Children, inspired by my master’s thesis, a qualitative project exploring how Black activist mothers aligned with the #BlackLivesMatter movement resist racism through childrearing (Watts, 2018). This theorizing of Black motherhood through CRS is fashioned from key threads of Critical Race Theory (CRT) (Delgado & Stefancic, 2017), Pedagogies of the Home (Delgado Bernal, 2001), Oppressed Family Pedagogy (Hughes, 2005) and the Cycles of Socialization/Liberation (Harro, 2000).

My aim is to offer a conceptualization of racial socialization that is informed by CRT in: (1) centering the narratives and knowledge of Black activist mothers as experts of their own experiences; (2) naming the pervasiveness of racism (and intersecting forms of oppression) in the lives of Black mothers (3) theorizing Black Motherwork as activism; and (4) asserting how the work of Black mother organizers can be understood as transformative, liberatory and developmentally responsive.

Read this issueMethodological Briefs

Finding Consuelo Rivera: Linking Critical Race Theory and History

LLuliana Alonso

University of California, Los Angeles

William Tate’s (1997) seminal article posed an important question to the field of education by asking “do we in education challenge ahistorical treatment of education, equity, and students of color?” (p.235). Using Critical Race Theory (CRT) in education (Solórzano, 1998) as a framework, this research brief illustrates innovative methodological approaches using primary sources to unearth and examine the historical educational experiences of Students of Color. Specifically, it highlights the educational trajectory of Consuelo Rivera, a Chicana student within UCLA’s Graduate School of Education in the first half of the twentieth century. Mexican children during this time period were perceived as intellectually handicapped, often attributed to their culture, language and heredity (González, 1990). This in turn led to educational programs for Mexican students that strictly emphasized vocational, non-academic training. Consuelo’s story helps us challenge deeply rooted assumptions of Mexican students’ intellectual inferiority and highlights the resiliency of this community over time.

Read this issue

Muxerista Portraiture: Portraiture with a Chicana/Latina Feminist Sensibility

Alma Itzé Flores

Loyola Marymount University

Moved by Gloria Anzaldúa’s (1990) call for nueva teorías, in this research brief I outline what I refer to as muxerista portraiture. As a meXicana (pronounced me-chi-cana) scholar who examines Mexicana/Chicana mother-daughter pedagogies, I argue for the partnership of portraiture (Lawrence-Lightfoot, 1983) and Chicana/Latina feminist theory (CLFT) (Delgado Bernal & Elenes, 2011). My goal is to offer a thoughtful and deliberate methodology that borrows from these two theories and not an alternative or replacement for one or the other. I begin by briefly discussing what portraiture and CLFT are and how I bridge the two, I then highlight the five contours of muxerista portraiture, and conclude with areas for future research.

Read this issue

Conceptualizing a Critical Race Educational History Methodology

Ryan E. Santos

University of California, Los Angeles

Michaela J. López Mares-Tamayo

University of California, Los Angeles

LLuliana Alonso

University of California, Los Angeles

In their foundational piece on Critical Race Theory (CRT) and education, Gloria Ladson-Billings and William F. Tate (1995) wrote, “Historically, storytelling has been a kind of medicine to heal the wounds of pain caused by racial oppression” (p. 57). As Critical Race theorists, we are especially invested in understanding how those actions relate to Students of Color and their educational histories. Powerful scholarship documents the persistence of unequal educational institutions, policies, and practices for Students of Color, along with the constant struggle by Communities of Color for more equitable learning opportunities (e.g. Anderson, 1988; García, Yosso, & Barajas, 2012; MacDonald, 2004; Pak, 2002; San Miguel, 1987/2001; Siddle Walker, 1994).* Such work underscores the importance of history in establishing generational links between People of Color who presently endeavor for justice and our predecessors with whom we share this journey. In this brief, we draw inspiration from the aforementioned scholarship and CRT in education literature (Ladson-Billings & Tate, 1995; Solórzano, 1998) to offer guiding principles for students, community members, practitioners, and scholars interested in telling the stories of People of Color in their own neighborhood schools over time. Those principles build a methodology for documenting the educational experiences of Communities of Color that we call Critical Race Educational History (CREH).

Read this issueThe Crits Briefs

Asian American Critical Race Theory: Origins, Directions, and Praxis

Edward R. Curammeng

University of California, Los Angeles

Tracy Lachica Buenavista

California State University, Northridge

Stephanie Cariaga

University of California, Los Angeles

Asian American Critical Race Theory* is one of numerous group-specific Critical Race Theory (CRT) movements that emerged to address the complex racialization of people of Asian descent in the United States. In particular, Asian American Critical Race scholars document a legacy of state-sanctioned, anti-Asian discrimination and violence, and problematize the marginalization of Asian American perspectives in Critical Race work (Chang, 1999; Matsuda, 1993). Education scholars have applied Asian American Critical Race Theory (AsianCrit) to discern how formal institutional policies and informal social practices impact the racialization of Asian Americans as model minorities and perpetual foreigners, and the subsequent treatment of Asian Americans in education. In this brief, we review Asian American jurisprudence and AsianCrit in education, and offer insight regarding future directions for Asian American Critical Race Theory.

Read this issue

Revisiting BlackCrit in Education: Anti-Black Reality and Liberatory Fantasy

kihana miraya ross

Northwestern University

While Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a theory of race and racism more broadly, it enters the fields of both legal studies and education (at least implicitly) as a Black theorization of race. In other words, in its initial formulation, CRT specifically attempts to make sense of and respond to anti-Black racism’. In response to a perceived Black-white binary? in CRT, other “racecrits” emerge such as LatCrit, AsianCrit, and TribalCrit; these “crits” serve to address the specificity of racial oppressions faced by non-Black People of Color. The absence of a BlackCrit then, either meant that CRT was considered the same thing as a Black critical theory, or that a theory of race and racism was enough to encompass the experiences of Black folks in the United States. Although CRT may have privileged the experiences of African Americans at its inception, in conceptualizing BlackCrit, my colleague Michael Dumas and I, problematize the notion that CRT could (or should) suffice for theorizing blackness and antiblackness. In this brief, I explore BlackCrit as a Black critical theory within and in response to Critical Race Theory and offer insight into the utility of BlackCrit as a theory of (anti)blackness in education specifically.

Tribal Critical Race Theory: Origins, Applications, and Implications

Dolores Calderón

Western Washington University

Tribal Critical Race Theory (TribalCrit) was developed by Bryan Brayboy as a framework to understand the complex experiences of Indigenous peoples in education. Influenced by Critical Race Theory in the law and the subsequent application of CRT in educational work, TribalCrit addresses both the racialized and unique political status of Indigenous peoples as members of sovereign nations.

Read this issuePedagogical Briefs

Re-defining Counterspaces: New Directions and Implications for Research and Praxis

Socorro Morales

University of California, Los Angeles

I spent two years as a researcher and educator collaborating with elementary aged Brown youth in creating, developing, and sustaining a Critical Race Counterspace within their elementary school. Drawing from Critical Race Theory (CRT) scholars within the field of education, I initially understood counterspaces as “sites where deficit notions of People of Color can be challenged” (Solórzano, Ceja, & Yosso, 2000, p. 70). In thinking about this definition, I sought to co-create a counterspace with Brown youth that would allow them to reimagine what “schooling” or education could look like, given the dismal state of K-12 educational curriculum for youth of color (Valenzuela, 1999).

While CRT provided me with a basis to understand and develop counterspaces, I recognized in my work with youth that CRT scholars had not yet theorized what it meant to make sense of the tensions, contradictions, and growing pains of co-creating a counterspace. As a Chicana scholar with a Chicana feminist sensibility, I drew heavily from Chicana/Latina feminisms and in particular the work of Gloria Anzaldúa, to help me theorize these tensions. Thus, this brief highlights the theoretical and practical implications of braiding together (Delgado Bernal & Alemán, 2016; Gonzalez, 2001) CRT and Anzaldúa’s Borderlands’ to make sense of the challenges that are inherent within counterspaces.

Through my own research and praxis with young Brown youth, I was able to formulate a new definition of counterspaces as: dynamic sites where people on the margins engage with one another in critical discourse, bring their whole (and multiple) selves, challenge each other, and make sense of the multitude of contradictions they embody, which are always present, as a means of undergoing moments of transformation. Below, I outline how I conceptualized my braiding together of CRT and Anzalduan thought which informs my understanding of counterspaces, followed by what this conceptualization means for both theory and practice.

Read this issue

50th and 25th Anniversaries: Historical Lessons of Chicana/o Student Activism in Los Angeles, CA

José M. Aguilar-Hernández

California State Polytechnic University, Pomona

Dolores Delgado Bernal

California State University, Los Angeles

In the spring of 2018, two anniversaries were commemorated in the history of Chicana/o/x* student activism in Los Angeles, California: the 50*’ anniversary of the 1968 Blowouts and the 25* anniversary of the 1993 hunger strike for a Chicana/o Studies department at UCLA. Although separated by time and space (the blowouts were in Eastern Los Angeles and UCLA is in Westwood) both events are part of a broader history of resistance, demonstrating that Students of Color are historically committed to resisting racial inequality in educational institutions. For example, in 1951, Barbara Johns organized Black students in a walkout to protest separate and unequal schooling conditions in Farmville, Virginia (Turner, 2004) and in 1968, the Third World Liberation Front led strikes to establish the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University and the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley (Muñoz, 2007). We situate these historical examples of student activism within the field of Critical Race Theory in Education, as examples of transformational resistance, because of the students’ critique of oppression and commitment to social justice (Solórzano & Delgado Bernal, 2001). The student activists of the ’68 Blowouts and the ’93 hunger strike brought change to Los Angeles and beyond, inspiring future generations of students to demand social justice in their schools and communities.

Holistic Critical Race Pedagogies: Embracing Wholeness Through Resiliency Circles

Heidi M. Coronado

California Lutheran University

Critical Race Pedagogies (CRPs) allow us to engage in liberatory pedagogies for students who have historically been at the margins (Lynn, 1999). As a formerly undocumented, first-generation, Guatemalan student and academic with Mayan roots, I have seen society’s assimilationists ideologies demand marginalized populations to adhere to specific norms based on colonial legacies that are often enforced through Euro-centric curriculum, policy, and pedagogical practices in schools (Lynn & Dixson, 2013). I argue that a CRP allows us to combat the continued trauma-inducing silencing of the voices and experiences of Students of Color (Smith-Maddox & Solórzano, 2002; Yosso, 2005). Transformative pedagogical practices are needed to provide students with the opportunity to engage in critical thinking development that provides them with the language and tools necessary to name their lived experiences. As a student of Mesoamerican and indigenous healing practices, I also argue that we must pay careful attention to the process in which students engage with critical material.’ It is not sufficient to provide students with theoretical tools and concepts, but we must address the whole self and being of the students. In this piece I offer a pedagogical framework, which I am naming Resiliency Circles, that is useful in fostering spaces that honor students’ experiences in becoming critically aware through a holistic lens.

UndocuBruins: Critical Race Theory in the Forming of Resources for Undocumented Students

Yadira Valencia,

German Aguilar-Tinajero,

Eva Amarillas,

Joel Calixto,

Katy Maldonado,

& Julio Reyes

University of California, Los Angeles

This research brief hopes to reach institutional agents and advocates who wish to implement research programs and resources for undocumented, first-generation, low-income undergraduate students-through the critical and intersectional lens of Critical Race Theory (CRT). By intentionally creating programs through CRT, we can see how students’ multiple identities and lived realities impact the research they develop, and the processes needed to support students through their research and graduate school endeavors. Yadira Valencia, was fortunate to be the coordinator for the UndocuBruins Research Program at UCLA from 2014 to 2018. Growing up in a mixed-status family, Yadira witnessed her eldest-sister experience academic road blocks due to her undocumented status. This experience emphasized for Yadira the necessity for academic resources further solidifying her commitment to this work. It is critical to support the trajectories of undocumented scholars; especially when they are still barred from federal and state resources. This brief discusses UndocuBruins and the ways in which using CRT has and will continue to center the lived experiences of undocumented students.

Revisiting Latina/o Transfer Culture: Recent Trends and Implications for California

José Del Real Viramontes

University of California, Riverside

Patricia A. Pérez

California State University, Long Beach

Miguel Ceja

California State University, Northridge

Community college continues to be a central entry point for underrepresented and disadvantaged students into postsecondary education (Velasco, et al., 2024). For instance, Latinx¹ students may begin their postsecondary education at a community college because they are placed in a non-college track throughout their K-12 education career (Gaxiola Serrano, 2017), are uninformed about the college process due to the limited guidance they receive from school personnel (Vega, 2018), they cannot afford university tuition, and/or do not have the English language skills necessary to succeed at a four-year institution (Castro & Cortez, 2017). For first-time college-going, Latinx college students, the community college serves as an important pipeline into higher education. Over 60% of first-time college-going Latinx students in the U.S. enrolled at a community college during the Spring of 2022 (National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, 2022). Further, Latinx students who begin their postsecondary education at a community college report aspiring to earn a bachelor’s degree via transfer and recognize the community college as their only choice in this process (Salas et al., 2018).